The Boardroom Table vs. the Tree

Same Material, Different Power

By Lindsay Bridge, Director, First Nations Economics

Where Decisions Happen Matters

Power doesn’t just sit in people. It sits in places. In rituals. In where and how we choose to talk, listen, and decide. For most Western structures, that power is concentrated at the boardroom table, polished wood, formal chairs, and glass walls. It’s the space where deals are struck, funds are allocated, and futures are shaped.

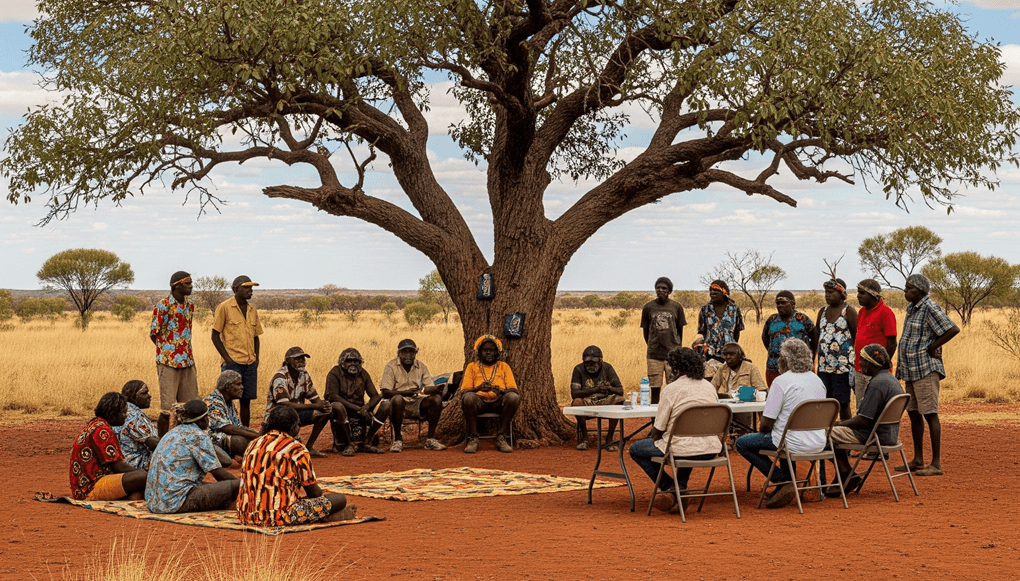

But for First Nations people, power has never been confined to that setting. Our boardroom has long been the open space beneath the tree, on Country, in conversation, in community. It’s where elders have gathered, truths have been spoken, stories spoke of identity and leadership has passed from one generation to the next. It’s not just symbolic. It’s sovereign.

And here’s the thing most people miss: the boardroom table and the tree are made of the same thing. Yet, one is more legitimate.

The Tree Is Not Less Than the Table

There is an unspoken assumption in modern economics and governance that legitimacy resides indoors. That the formality of a table, a chair, and a written agenda somehow means decisions matter more.

But here’s an important thing to consider: the tree was the first boardroom. Before corporate governance codes and performance reviews, there were gatherings under canopies, where silence was as powerful as words spoken, where people spoke from the heart, not from their roles. It is also where the outcomes weren’t just economic but also relational, spiritual, and intergenerational.

Our mobs didn’t need to prove legitimacy in reports. The legitimacy came from responsibility.

Responsibility to Country. To people. To legacy.

This is where our governance begins, and it doesn’t need a lanyard to be legitimate. Yet today, those who hold the pen on policy or the purse strings often treat the outdoor boardroom as informal, quaint, even. They arrive on Country, schedules tight, expectations set, and sit at a boardroom table brought with them, literal or symbolic. Then, they ask the mob to translate generations of cultural knowledge, pain, truth, and aspiration into language that fits a framework. Something that can be captured in a PowerPoint slide, compressed into a KPI, or justified in a budget narrative.

What gets lost in that translation is not just depth, it’s direction. Because when you remove a story from its rightful place and turn living knowledge into bullet points, you’re not engaging; you’re extracting. Extraction is precisely what impacts integrity.

Whose Comfort Defines the Conversation?

I have seen discomfort arise when decision or policy makers are asked to step out from behind the boardroom table. Because the table is more than furniture, it’s a symbolic barrier. An object of formality. It can be a place to hide behind when the conversation gets real.

Throughout my decades of experience in engagement, I’ve found that change from engagements doesn’t happen in safe spaces for those who are engaging. It occurs in truth spaces. Yet, many of the most critical conversations about First Nations’ futures are still being held in the wrong places.

So the challenge; If the boardroom table and the tree are carved from the same wood, why not meet the mob at the source? Sit with them where reality speaks its language, where decisions are grounded in Country, community and consequence, not just policy, paperwork and process.

Reframing Authority: From Formality to Relational Governance

Power, in its most valid form, isn’t just about control. It’s about accountability. In First Nations governance, accountability has always been a relational concept. We don’t make decisions in isolation. We make them in the web of kinship, responsibility, and cultural law.

The boardroom has rules, yes, but often, those rules are arguably about protecting liability than strengthening responsibility. In contrast, the tree offers no such insulation. What you say under the tree and on Country must be lived. It’s heard by elders, witnessed by the community and remembered by land.

If we are serious about shifting power, not just sharing optics, then the systems we use to make decisions need to reflect relational accountability, not just operational efficiency or political palatability.

The Path Forward: Bring the Table to the Tree

Here’s the opportunity: it’s not about destroying boardrooms or rejecting formal structures altogether. It’s about expanding our definition of legitimacy.

We need economic systems and governance frameworks that are not afraid to step into cultural spaces. Systems that are humble enough to sit in a circle, not just across the boardroom. Respect that an agreement made under a tree, in full view of Country and community, can hold as much, if not more, weight than any contract typed in a capital city office.

Could we shift from asking First Nations people to leave their governance at the gates of Western institutions, models, and practices? Instead, we become more willing to walk out of our offices and sit down, literally and symbolically, on Country.

Imagine what would change if economic policy and structural strategy design began with a yarn, not a ‘terms of reference’ document. What if investment committees started with cultural protocol, not just financial risk analysis. This will ensure we treat the tree with the same power as the boardroom table.

The Power of Returning to What Was Never Lost

This isn’t a symbolic or an aspirational idea. It could be a radical one for some, as it challenges people and systems to step outside their comfort zones, established structures, and assumptions of authority or leadership. It reminds us that real impact and power have never needed walls or titles. It requires storytelling, knowledge, relationships and place.

Of course, some of this is a metaphor, and some of it is entirely practical. The truth is, I’m not asking for the boardroom to be abandoned. I’m asking for you consider ways to evolve. To recognise that new systems of engagement don’t have to replace the old, they can expand upon, deepen, and make them more authentic.

There’s a powerful opportunity here to shift how decisions are made and what is valued.

We are able to ensure you ready to explore what that could look like, whether through new approaches, better systems, or more authentic partnerships, First Nations Economics is here for that conversation.